Let me start by telling you three stories.

Gregor MacGregor: An adventure into the unknown

In 1820, a swashbuckling Scottish soldier named Gregor MacGregor (maybe the most Scottish name of all time) received eight million acres – an area larger than Wales – of Central American territory from the king.

MacGregor named the land Poyais after the native Paya people. He even created a constitution, a tricameral parliament, and commercial and banking systems.

MacGregor, ever the opportunist, then launched an aggressive campaign to attract investment in Poyais, using national newspapers, publicists, and even ballads sung on the streets of London, Edinburgh, and Glasgow.

Hundreds of people signed up to emigrate, enough to fill seven ships. MacGregor raised what would today be equivalent to $3.6 billion in securities, bonds, and real estate sales.

Victor Lustig: Selling the Eiffel Tower

Fast forward to 1925, when an enterprising Austro-Hungarian named Victor Lustig read about France’s difficulties maintaining the Eiffel Tower.

Seeing an opportunity, he held a confidential meeting with a group of top scrap metal dealers in an expensive Parisian hotel. He introduced himself as the Deputy Director General of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs and claimed that the French government, overwhelmed by upkeep costs, was considering selling the Eiffel Tower for scrap.

One of the dealers, André Poisson, offered Lustig a bribe – about $1.1 million in today’s money – for the exclusive rights to buy the tower. Lustig graciously accepted.

Shinichi Fujimura: Unearthing secrets

In 1975, an amateur Japanese archaeologist named Shinichi Fujimura stunned the academic world with what he claimed were the world’s oldest Paleolithic stone artifacts.

His reputation earned him the nickname “the archaeologist with divine hands.” Despite having no formal training, Fujimura was appointed head of a global NGO focused on stone tool culture research.

What do these stories have in common?

So, what do all three of these historical achievements have in common?

Well, for one, they were all cons.

When settlers arrived in Poyais, they discovered it was nothing but desolate land. MacGregor’s scam led to the deaths of more than 150 people and the financial ruin of countless others. Meanwhile, MacGregor had disappeared to Venezuela.

Lustig wasn’t a French minister and had no right to sell the Eiffel Tower. As you may have noticed, it wasn’t sold for scrap.

Fujimura, hailed as a brilliant archaeologist, was later found to have planted fake artifacts at 42 excavation sites.

Product marketing scams

“But Jason,” you might be wondering, “What does any of this have to do with product marketing?” Fair question.

A few years ago, I led a product marketing organization focused on fraud solutions (preventing fraud, not causing it!). During that time, I spoke to numerous fraud experts. I even met Brett Johnson, a notorious cybercriminal who was once on the FBI’s most-wanted list and now speaks on the psychology and motivations of online fraudsters.

I quickly realized that the same psychological principles behind fraud – whether in account takeovers, impersonation scams, or cons like the ones we’ve just explored – are present in many other areas of life, from politics to corporate America.

In this article, we’re going to dive into the underlying motivations and cognitive biases that often lead us down the wrong path. My goal is to help you identify and short-circuit these biases before they negatively impact your product marketing efforts.

Specifically, I’ll cover three common marketing scams:

- The scam of expertise

- The scam of authority

- The scam of busyness

I’ll walk you through the psychological impulses behind each of these scams and share what you can do to combat them.

Just a quick note before we dive any deeper: I’m not speaking on behalf of any organization in this article. All the opinions you’ll read are my own.

Let’s get into it.

Scam #1: The scam of expertise

I want to start by dispelling a common myth about scams – that they mostly target elderly individuals with low media literacy.

You might be surprised to learn that the group experiencing the highest growth in fraud victimhood over the last few years is actually twenty- to thirty-nine-year-old middle- to upper-class professionals.

Why is that the case? Well, there are at least two reasons. First, that’s where the money is – so, naturally, that’s where fraudsters go. Second, every researcher on fraud trends says the same thing: Being a victim of fraud is often tied to the belief that you’re too smart to fall for it.

That belief in your own intelligence, expertise, and invulnerability is exactly what fraudsters exploit. This connects directly to the scam of expertise.

The trap of product expertise

I’ve heard well-meaning product marketing leaders say that to be an effective product marketer, you need to become best friends with the product team and deeply understand your product.

I couldn’t disagree more.

Becoming a product expert is a trap, and it can make you a less effective product marketer. Let me explain.

Product owners love their products. Their products are their babies. Every hair on their head, every crumb on their overalls, is beautiful and precious. That devotion to the details of their product is exactly what you want from a successful product owner. The trouble comes when product marketers buy into that hype.

Your job as a product marketer isn’t to be a faithful transcriber of every detail the product owner finds most exciting. That’s a product-centric view of the world. It assumes that humans are rational decision-makers, and if customers simply learn about how great your product is, they'll rush to buy it.

When product marketers fall into this trap, they’ll start parroting back the same jargon the product owner uses. That’s a huge red flag.

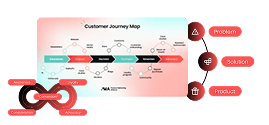

An effective product marketer should stand in for the customer. And guess what? Customers don’t care about your product. What they care about are their problems – the ones they’re dealing with at work, the ones their bosses are demanding solutions for.

The superpower of ignorance

I constantly remind my team that there’s a superpower in ignorance. It allows you to approach a market problem with a blank slate, just like a customer would.

A product marketer's role is akin to a journalist: an impartial observer digging beneath the surface to unearth the real story the customer would actually be interested in.

In practice, this means asking “why” – or its slightly more assertive cousin, “so what” – five times. Not like an annoying toddler, but as a genuinely curious and neutral observer, eager to get to the heart of what matters.

Digging for the real story

Let’s say a product manager comes to you and says, “Great news! We’ve just implemented an API feedback mechanism in our 2.0 call center authentication product, and we need to get the market excited. We need a press release, an asset sheet, and sales team training. Let’s go, go, go!”

Your response might be: “Great. Well, what’s exciting about it?”

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn

.svg)