Reaching Product-Market Fit (PMF) is one of a few critical milestones for new products and early-stage companies. In fact, most venture-backed companies won’t get funding past Series-A until they demonstrate PMF.

However, funders and boards know that Product-Market Fit can be elusive if the right metrics aren’t used to confirm “fit” – too many founders are enamoured by “vanity metrics” rather than core PMF metrics that show solid traction.

So, what is (and isn't) Product-Market Fit (PMF)? It’s misunderstood because there are so many ways to think about it - most of which are qualitative.

In my experience, PMF can be quantified, and clearly distinguished from those “vanity metrics”. To that end, I’ll be unpacking the following product-market fit myths, whilst also providing comparisons to less-important metrics:

- PMF is never static

- PMF isn’t binary

- PMF ≠ PLG

- Early adopters don’t imply PMF

- Rising sales aren’t always a sign of reaching PMF

- PMF isn’t about every audience

- PMF must result in an exchange of value

Product-Market Fit is never static

The value of your product will change over time, and the needs/expectations of customers will change too.

Products evolve, markets mature, and competition innovates. Expect that your product may fall out of PMF at some point, and protect against it by constantly monitoring key metrics and customer feedback.

Key takeaway: Product-Market Fit has to be continuously monitored, tracked, and adjusted to detect changing product and market forces. Maintaining market fit means tracking and evolving feature usage, how they meet customer needs, and sensing where those needs are evolving.

Don’t be afraid to confront the Innovator’s Dilemma - when you see an oncoming threat where your product may fall out of market fit.

Product-Market Fit isn’t binary

PMF is sometimes thought of in yes-or-no terms. The reality is that it's about the degree to which customers find value and the degree to which they’re eager to buy/use.

Neither of these metrics is binary. However, the spectrum of value and market fit can be measured and monitored in a number of ways, and you should constantly evaluate the trends.

Key takeaway: You can track the degree to which you are in PMF using the Sean Ellis test, as well as using specific customer engagement metrics over time.

Survey different segments of your customers, especially “super users” and “high-expectation customers”, who’ll give you an early indication that you’re in your PMF sweet spot, and/or losing ground in certain areas.

Product-Market Fit ≠ Product-Led Growth

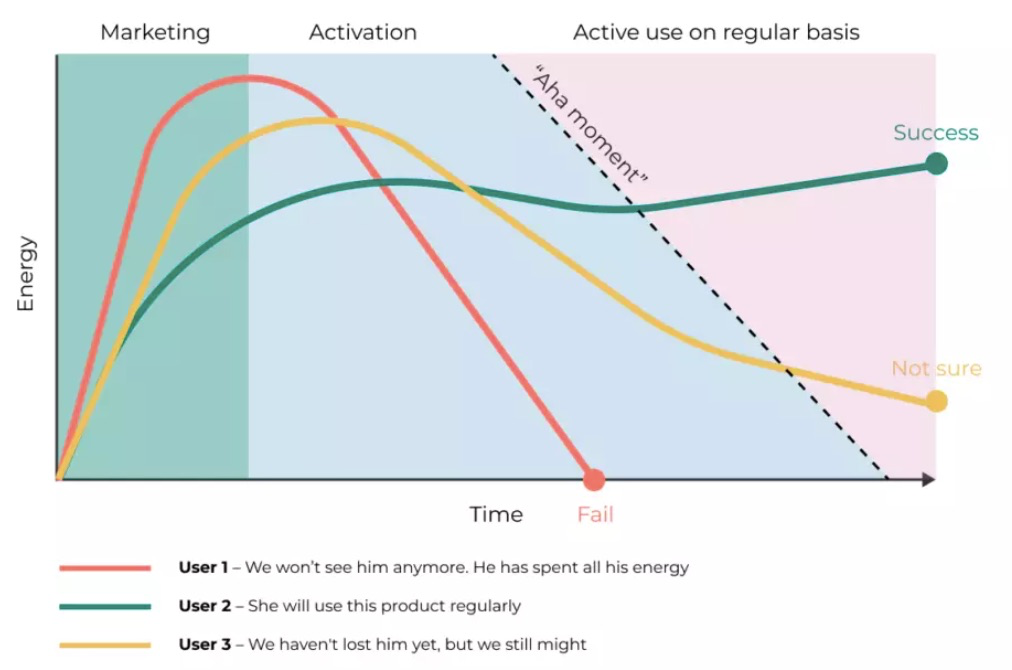

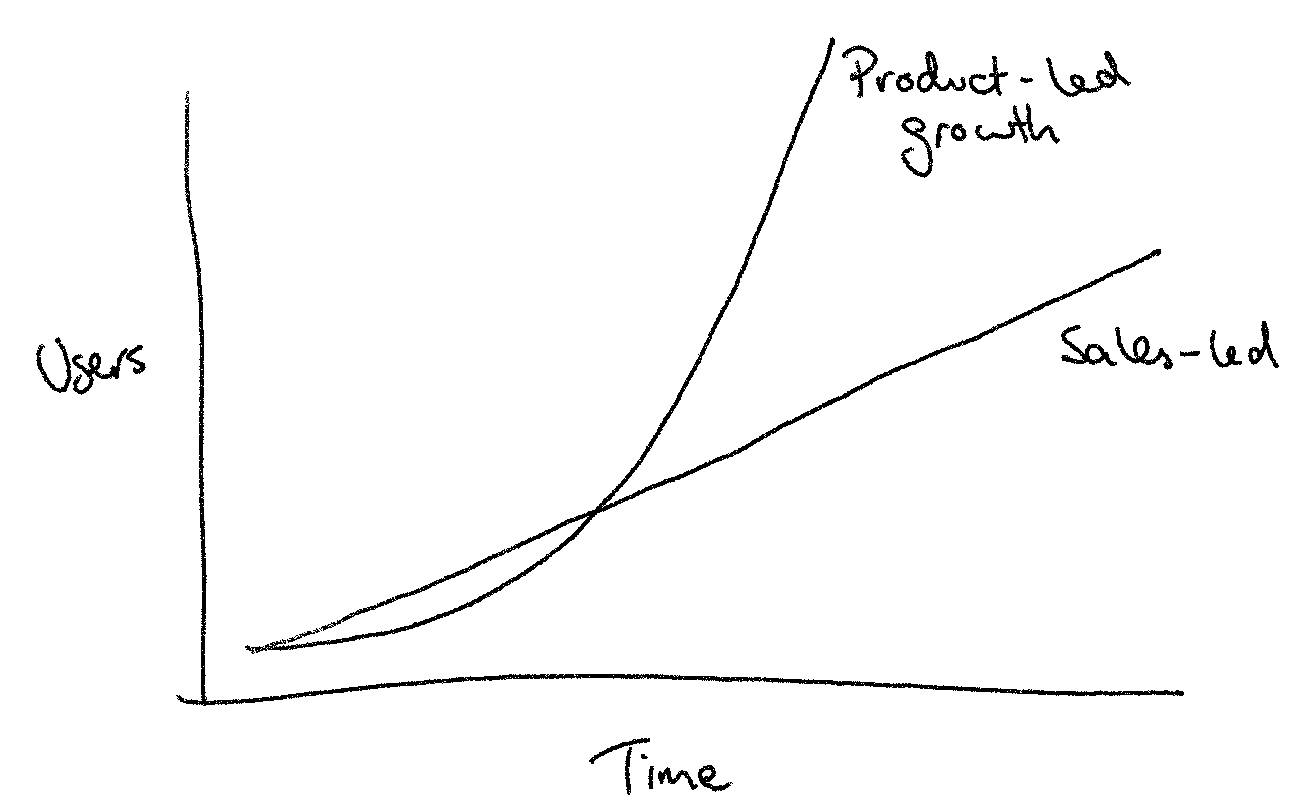

Product-Led Growth (PLG) is not equivalent to Product-Market Fit. PLG is a method to drive trial and adoption, so it’s possible to have a product that’s quickly and eagerly adopted (a “shiny new” experience for users) but doesn’t ultimately fit the definition of PMF.

Key takeaway: It’s certainly a great idea to design products using a PLG mindset. But first, invest in finding and quantifying Product-Market Fit. Only then should you work to extend PLG methods to drive adoption.

Otherwise, successful first-time PLG-based adoption/sales could result in high levels of abandonment, defections & churn.

All-to-often companies end up with a massively effective sales-led effort, only to find later a lack of renewals and upsell due to poor long-term product-fit.

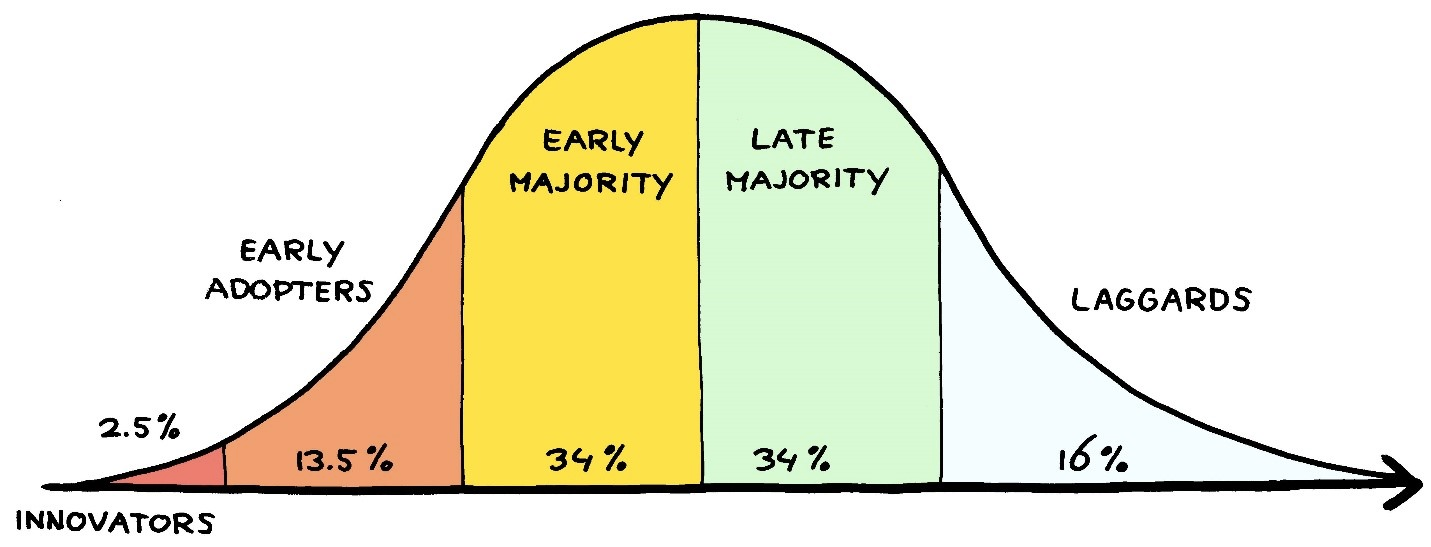

Early adopters do not imply Product-Market Fit

Don’t assume that your early adopters and initial hand-selected customers indicate PMF.

Generally, they might buy because of relationships, but not necessarily due to PMF. But they can serve as a great sounding board for how to better adjust your product and target audience.

Key takeaway: Remember that those initial buyers were probably personally selected, closely educated in your product, and hand-held through the buying process.

Or, they're true early adopters and might not represent the mainstream buyer you want/need. What *is* relevant is whether buyers (early or not) keep using your product, engage in it more deeply, and can’t live without it.

The true signs of PMF. Early adopters can, however, give you hugely-useful input in what they find valuable, where to take your development, and who else to target.

Rising sales aren’t always a sign of reaching Product-Market Fit

A secret known to most VCs and board members isn’t to be overly impressed by growing sales. True, ramping sales is a fantastic sign of success.

The VCs know to dig deeper to see if those sales result in repeat business, stickiness, upsell, and low churn. Hit those secondary numbers, and then it’s a home run.

Key takeaway: Similar to the PLG example, dig deeper into what happens with customers *after* the sale. Use metrics like active use, engagement, churn, and net-dollar retention. You could still be a company with rising sales but have customer loss that’s out-stripping your revenue growth.

Product-Market Fit isn’t about every audience

There needs to be a specific, definable market segment that should be the focus of your product and each feature set.

Ultimately, your product should address those segments’ needs extremely well, and drive repeat use and engagement within each one. PMF doesn’t promise fit for *every* audience… in fact, it generally drives a narrow focus on serving specific segments incredibly well.

Key takeaway: Trying to be everything to everyone is a strategy that ends up offering only a little bit to a very few - and excelling in nothing.

You can have PMF across various (even divergent) audiences, but it’s generally true only when the product has feature sets tailored to the needs of those specific users.

It’s best to design & target specific feature sets to different buyer segments, and then test those feature/segment pairings with achieving PMF.

Trying to gauge the PMF of a giant product across all available audiences at once will likely result in meaningless data. Think micro - not macro.

Product-Market Fit must result in an exchange of value

Even “freemium” products must result in an exchange of value at some point with an audience.

If there's no exchange of value, then you don’t have a business - nor a product. This is even true for open-source software - where the exchange of value is in the form of support and/or contribution back to the code base.

Key takeaway: Just because a “free” or “freemium” aspect of your product seems to have traction or success, remember that this is only a leading indicator for the business.

True PMF happens only if customers are willing to pay for your product. Keep in mind that there’re sometimes PMF business models where users aren’t necessarily the paying customers, for example, on social platforms where advertisers are the paying customers.

Conclusion

If you’re serious about measuring success, then get serious about being precise about achieving PMF. Know that it can be quantified, that it’s dynamic, and that it goes far deeper than fancy vanity metrics.

Challenge your marketing team to take a hard look at PMF-related goals and OKRs, and use your regular product marketing reviews to drill into whether you have sustainable PMF or not.

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn

.svg?v=4c397528de)