Product marketing is the driving force behind getting products to market - and keeping them there. Product marketers are the overarching voices of the customer, masterminds of messaging, enablers of sales, and accelerators of adoption.

PMMs are responsible for a variety of deliverables and are a fundamental part of the product lifecycle.

They’re the masterminds behind making product features appeal to the senses, whether that’s through email marketing, webinars, and other marketing functions, and are some of the world's most accomplished plate-spinners, playing a crucial role in ensuring products appease the company’s target customer.

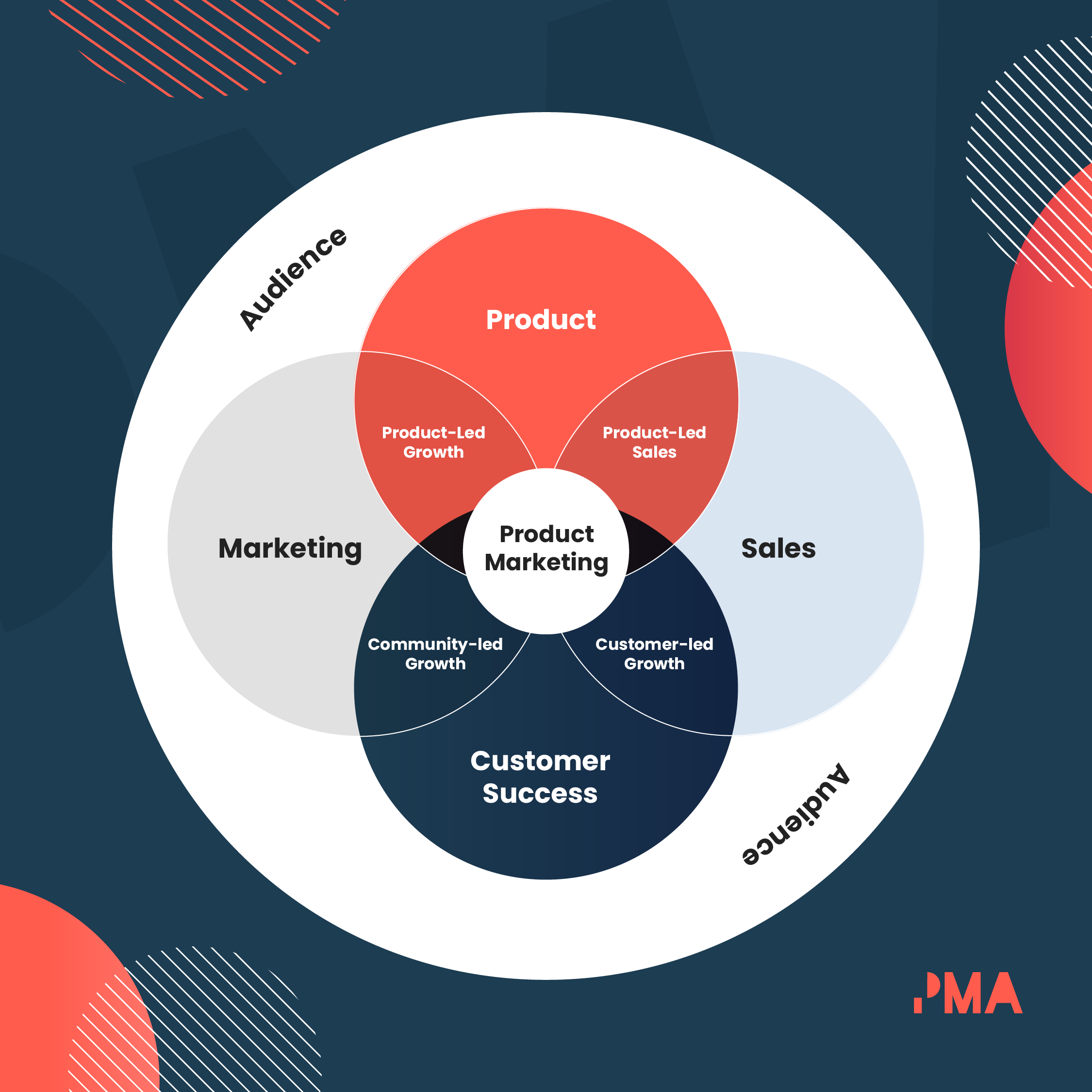

The role of product marketing: visualized

In six very simple circles, the role looks a bit like this:

The evolution of product marketing as a business function

The Product Marketing Framework

Product marketing sits at the heart, the intersection, and the core of all successful companies. PMMs collaborate with key teams such as the marketing team, sales, customer success, and plays a critical role in helping the business achieve its goals.

It's vital and exciting - but it can be a little complicated, but this is where the Product Marketing Framework comes in:

Our Product Marketing Framework covers all the necessary areas required to navigate the product marketing journey, from A to B to C to D... the list goes on.

The framework defines five fundamental phases of product marketing: discover, strategize, define, get set, and grow. We recommend familiarizing yourself with the full framework to really get to grips with each of the moving parts.

But in the meantime, here's a whistle-stop tour:

Discover - This is the stage in which you gather the info and insight to turn your assumptions into an educated hypothesis. Customer feedback and sussing out the competition are just two of the key elements involved - and they're both product marketing gold dust. ✨

Strategize - Whether it's product-market fit, your GTM plan, or your pricing, strong product marketing always comes with a strategy.

Define - This is all about identifying your personas and applying what you garnered from your discovery stage to shape customer journey and communications.

Get set - Here, it's time to harness all your hard work thus far with training, sales enablement sessions, and marketing campaigns so your team is equipped to take the GTM by the horns and run with it.

Grow - This is where your post-launch process needs to kick in, to ensure your product continues to flourish and evolve in its market.

Product marketing vs product management

There’s a lot of ambiguity around both roles, so you can be forgiven for confusing Product Managers (PM) with Product Marketing Managers (PMM), as many, many people do.

There are certainly some similarities, PMs and PMMs are all-rounders, who can effectively work across product, marketing, and sales. Both are responsible for product launches and both roles need to coordinate different teams within an organization to ensure that the product release is successful.

Check out the article below for more information:

What are some examples of product marketing?

“Product marketers are the people responsible for being able to deeply understand and therefore articulate what is different and better and remarkable about your offering.”

April Dunford, Founder of Ambient Strategy

One of the challenges of product marketing is that we’re surrounded by it 24/7 and yet people have a really tough time defining it.

The first step to understanding it might be understanding what it isn’t. Think of Coca-Cola’s polar bear commercials. There wasn’t any particular product push in there, the message was just ‘if you think of Coca-Cola, think of the largest living land carnivore and have happy thoughts’.

It didn’t matter if you buy a bottle of regular coke, a can of diet coke, or a Coca-Cola t-shirt. This is brand marketing. On the other hand, the Diet Coke break ads are pushing a particular product, Diet Coke, and this is (a small part of) product marketing.

But it doesn’t end with ads. Coke’s product marketers would have had to think about what the pricing of Diet Coke says about its position in the market:

- Is it a premium product that consumers are willing to pay more for?

- Should we sell Diet Coke in stores or through a mail-order subscription service? Should we sell them in 330ml cans or 500ml?

- Who are our consumers, the office ladies or the buff construction worker?

- Do people even like the taste?

After somebody at Coca-Cola’s labs came up with the formula for a cola with fewer calories all these questions and 1,000s of others needed to be answered and the answers need to feed back to the company so it can create products people want to buy, avoiding any ‘New Coke’-style mishaps.

Or, since the majority of PMA’s members are in the B2B SaaS space, imagine a company’s developers have come up with a new piece of marketing automation technology.

A product marketer might find there is a gap in the market for marketing automation amongst small businesses, so it will follow that the software should have a low price and flexible subscription options, and the website should make it clear that it’s for small businesses and there’s little need for enterprise-level after-sales care like dedicated customer contacts.

The insight that the particular technology the company made would fit best with small businesses will affect everything from the go-to-market strategy to the name, and it’s a product marketer’s role to bring that all together.

Get all the intel on this page as your very own FREE eBook. As a tasty bonus, you'll also get an exclusive article from Rockerbox's Maggie Tharp – usually just for subscribers. Snag your copy now!

Why is product marketing important?

Important? It’s not just important, it’s critical.

Your company is going to sell products and services. If it doesn’t it isn’t a company. Those products and services need to be things people actually want to buy, and they need to be priced so people will want to buy them.

Take Quibi for instance. This ‘two billion dollar faux pas’ is a classic example of the need for solid product marketing. The phone-only Netflix competitor tried to be the solution for a problem that didn’t exist: offering five-minute TV shows to be consumed as ‘quick bites’ during downtimes like waiting in line for coffee or the commercials in regular TV shows.

The problem: people already have a million ways to pass their time on their phones during that time that don’t cost $7.99 a month.

A smart product marketer could have prevented this disaster with a quick customer survey to show that people didn’t really want to watch more shows during shows; instead, they went to market not knowing who their customer was, what problem Quibi solved for them, or how to sell it.

This was not a company that was ‘customer obsessed’.

And after you have a solid product and you know customers for it are out there, product marketing allows you to:

- Learn about your competitors.

- Position the product in the market.

- Differentiate your product from others.

- Use customer feedback to improve it or create new products.

What is product marketing actually responsible for?

A product marketer’s responsibilities never fade and they’re at the heart of products and customers before, during, and after launch. Our 2024 State of Product Marketing report uncovered the most common tasks they work on:

- Product positioning and messaging (90.6%)

- Managing product launches (78.7%)

- Creating sales collateral (75.5%)

- Customer and market research (64.6%)

- Sales enablement (64.3%)

- Building personas (58.2%)

- Storytelling (55.3%)

- Competitive intelligence (56%)

- Website management (50.5%)

As we touched on a little earlier though, the role varies from industry to industry, company to company, and product to product, so what’s a priority for someone else might not necessarily be one for you.

What do we mean by that?

For one product marketer, creating sales collateral might make up 60% of their job and for another, it might account for just 25% of it. Because the role is still relatively new, many organizations are still finding their feet with it, which is one of the main causes of ambiguity.

So, let’s drill down into each of those responsibility areas in a bit more detail.

1. Product messaging and positioning

Having a great product is...great, but what’s not so great is trying to convince an entire market to buy it with one, blanket message. It just doesn’t cut the mustard and that’s where product marketers are instrumental.

The aim of messaging and positioning is to understand what does and doesn’t make your market tick and then frame your product in a way that resonates. In terms of templates, there are two pretty common, industry-wide documents that help with this: messaging hierarchies and positioning statements (spoiler, we have frameworks for each in our membership plans).

Collectively, these answer important questions like:

- Who’s the product for?

- What unique problems does it solve?

- Why’s it different to the competition?

- How does it benefit our audience?

2. Managing product launches

Whether it’s a small-scale feature update or a full-blown new product, launches are the cornerstone of the product marketing position.

We all know the iceberg analogy, right? Well, product marketers are the people responsible for that pristine tip effortlessly sitting above the water - all the while juggling the chaos that lies beneath.

The word ‘intersection’ is used a lot in product marketing and that’s because it’s exactly where the role sits, at the intersection of many departments - like sales, product, customer success, finance and engineering - ensuring each is up-to-speed, pulling their weight, and enabled.

3. Creating sales collateral

Sales collateral comes in all sorts of forms and the extent of what’s required will largely depend on the type of launch.

For example, a small feature update that only impacts a subset of existing customers might only need a tiny wording update on the website and brief huddle with Sales and Customer Success to share the details.

A new product, on the other hand, might require the whole hog - demo videos, battlecards, fresh messaging and positioning, completely new webpages, sales training - the lot.

If you’re new to the industry one thing worth bearing in mind is that creating powerful sales collateral is one half of the battle, getting customer-facing teams to actually use them is the other, so don’t overlook your delivery - useful article to help with that below. 👇🏻

Useful resource: 22 sales enablement tools for product marketers and How to get salespeople excited about your launch.

4. Customer and market research

Next up is the pre-work. Before, during, and after any type of launch, there’s research to be done.

- Who’s the target market?

- What are their requirements?

- What are their defining features?

- What do and don’t they like about our product?

- Why did they choose the competition over us?

- How do they think we can be even better?

- What nice things do they have to say that can be turned into a case study?

After all, without any of this, you’re as good as whacking your finger in the air and seeing what sticks.

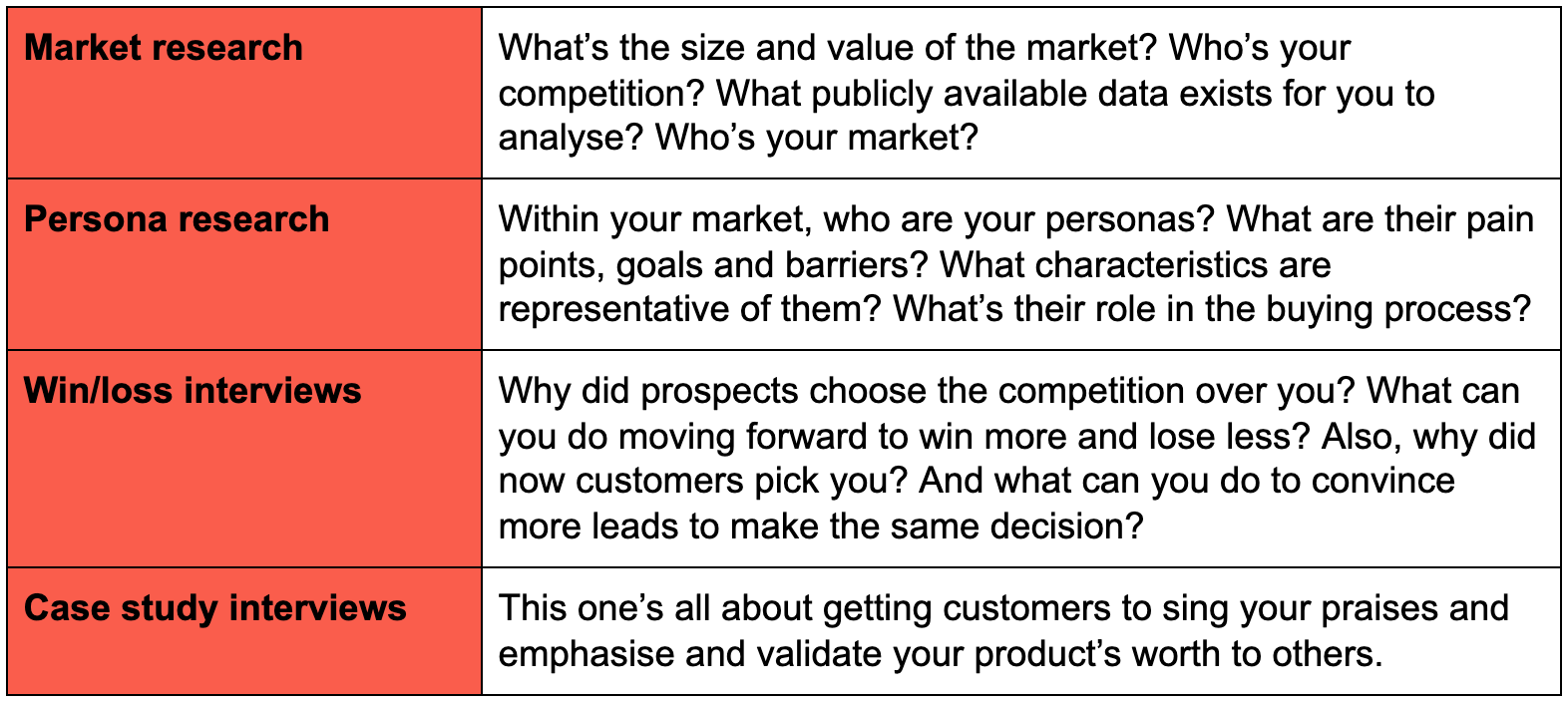

Now, when it comes to customer and market research there are a few different brackets:

On top of all this, there's competitive intel too, which, in Layman's terms, is the act of keeping on top of your competitors - i.e. positioning changes, price increases or decreases, new products or features, different marketing channels, etc.

This process is crucial in establishing yourself as the market leader and maintaining customer retention rates.

Useful resources: How to create buyer personas and How to conduct win-loss interviews.

5. Reporting on product marketing success

You could say KPIs are a bit of a grey area in product marketing - lots of people have them, many also don’t. To give you a flavor of what you’re looking at though, here are a few examples we’ve come across on Slack and in our podcasts:

- Number of daily, active, and/or monthly users,

- Overall revenue goals,

- Win rates,

- Usage of product marketing assets,

- Sales confidence - i.e. how confident the sales teams are in pitching your product,

- Marketing-qualified leads (MQLs) and sales-qualified leads (SQLs), and

- Customer satisfaction - using metrics like NPS scores.

6. Content marketing

Content marketing could be anything from blogs, whitepapers, and case studies to social media posts, product guides, and sales one-pagers.

We touched on it a little bit earlier, but the amount you’ll need to channel your inner-wordsmith will depend on the company’s setup. If there’s a team of copywriters built-in, odds are, you won’t need to take ownership all the time.

Anyway, naturally, some product marketers feel more comfortable with their copywriting skills than others and we’ve seen a fair few requests for course recommendations around this - here are a few we shared in a round-up a few months ago.

7. Managing the website

There’ll be exceptions, of course, but it’s rare that product marketing will be responsible for a company’s entire website. Instead, this is more a case of making sure:

- New features and products are reflected across the site,

- Elements relating to messaging and positioning are up-to-date and working,

- Everything is optimized - i.e. user experience (UX) and product usage, and

- In-app messages are scheduled and doing their job.

To name just a few.

8. Product roadmap planning

There’s no use sugarcoating it, some product marketers have a better deal than others when it comes to this but in theory, the customer and data-driven intel you gather should help shape product roadmaps.

For example, if you identify a meaningful percentage of customers crying out for feature Y, when will this be penciled into the pipeline? Or, if it’s already been decided product Z will be released in July, what tasks do you need to complete to be ready for that launch?

Although Go-To-Market strategies are the product marketer’s blueprint to success, the product roadmap is the overarching guide - after all, without that, you’ve not got anything to launch.

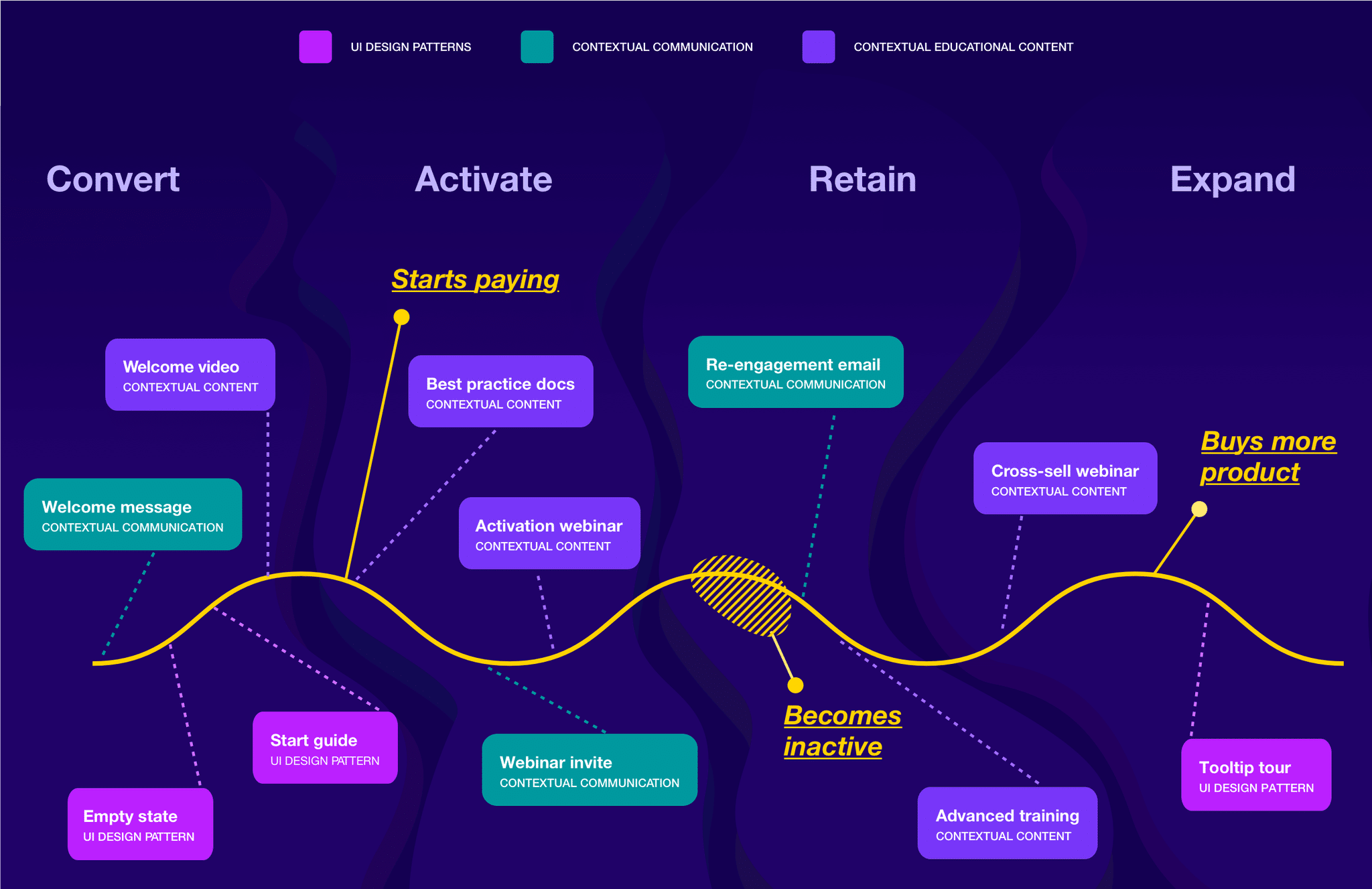

9. Onboarding customers

What happens after you bag that brand new customer? Nothing? Then they might not be around as long as you’d hoped. First impressions count and a solid onboarding process ensure everyone gets off to a good start and has everything they need to rinse all the value out of your product.

When it comes to the crunch, the mechanics of this will largely depend on the type of product you market - a B2B SaaS product will look very different from a B2C consumer goods product, for example. Focusing on the former, here’s a cadence framework from Intercom:

Does the perfect product marketer exist?

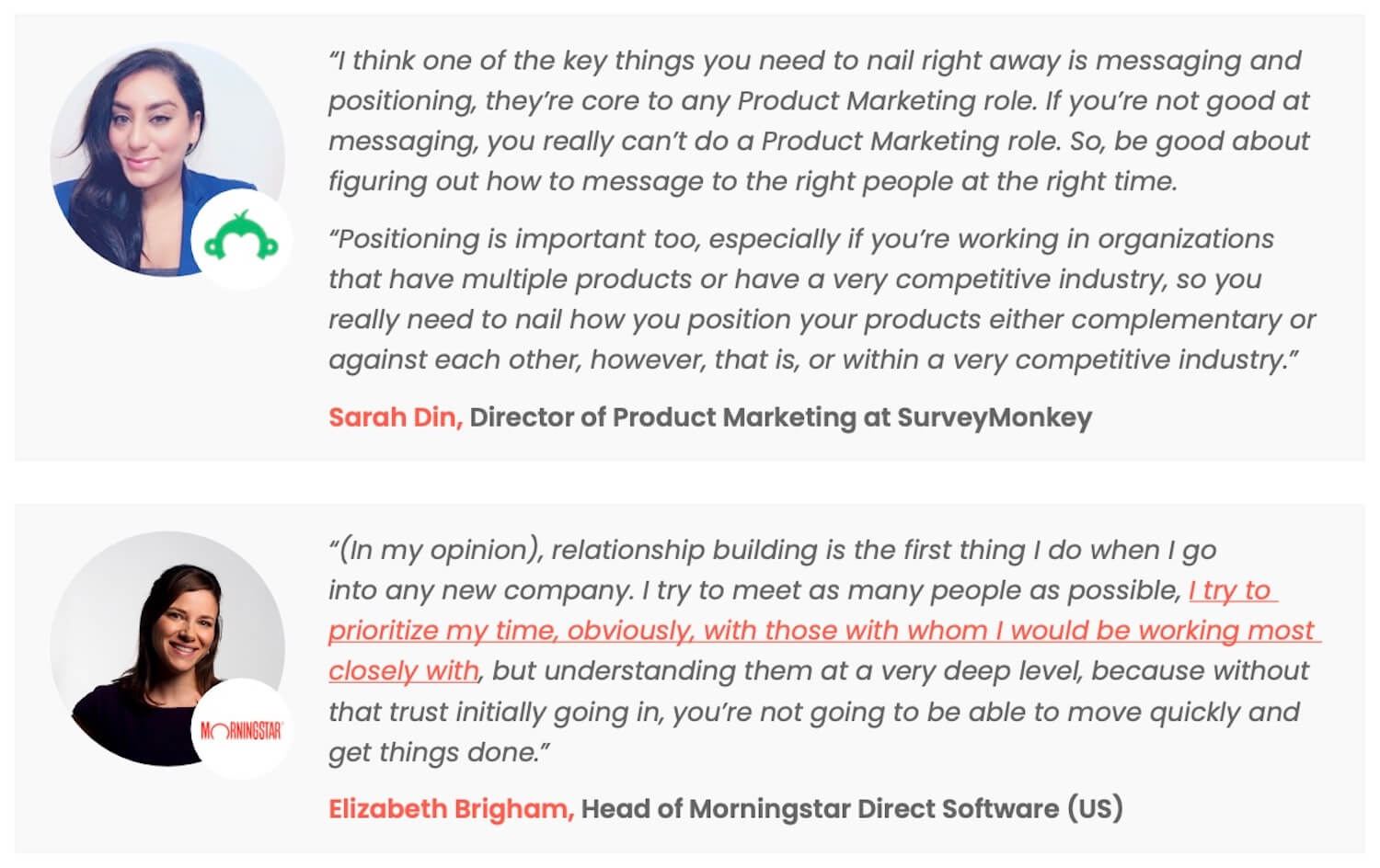

As part of our 2020 State of Product Marketing report, we asked a few industry experts what they think the key ingredients are for the perfect product marketer:

How does product marketing help sales?

Sales enablement is considered one of the most important functions of the product marketing role. This is an area that is dedicated to helping the sales teams with optimizing their sales technique to bring in the most potential customers possible and close more and more deals for the company.

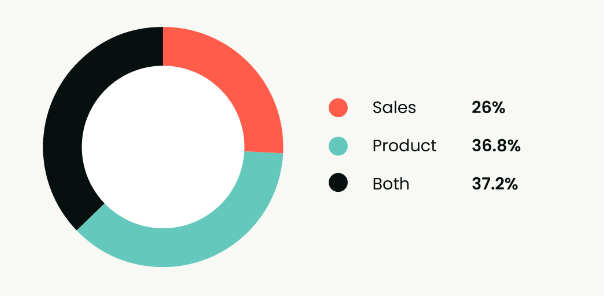

In the 2024 State of Product Marketing Report, 75.5% of PMMs said their core responsibilities involved creating sales collateral and updating internal documentation. However, the report also found that significant portion of respondents (37.2%) view their organizations as equally prioritizing both product and sales efforts.

A slightly higher percentage (36.8%) consider their companies to be more product-focused, while 26% perceive a greater emphasis on sales initiatives.

This distribution suggests that many organizations strive to strike a balance between product development and sales execution, but there’s also a slight trend toward product-centric approaches, potentially driven by factors like innovation, customer experience, and differentiation in competitive markets.

What is the most important part of product marketing?

Who better to answer this question than Product Marketing Alliance Founder & CEO, Rich King:

“In this day and age, it’s all too easy for companies to quickly spin up products and rival their competition with the same feature set, and even a similar story. IF no or low-code is the future though, product marketing is the antidote - if you want long-term, sustainable growth that is, anyway.

"There’s no doubt in my mind that product marketing should be the first marketing hire. PMMs aren’t nice-to-haves, or an extra layer to add to the department down the line, they need to be the foundation of the product and marketing team’s growth plans because they’re the ones advocating your customers and ensuring company outputs are in line with market needs.”

We also spoke to Elizabeth Brigham, Head of Product Marketing(Software) at Morningstar, and she summed this up perfectly, so in her words, not ours, here’s why:

“There are quotations out there that say anywhere between 80-90% of new businesses fail, whether that's a startup, new product line or new business being launched within an existing company.

“Some of those reports went back and asked CEOs or others within the C suite, well, why do you think you failed? The number one answer that comes back is product-market fit, and the way I break that down is by saying, well, you've got a product and a lot of people might think this is the cool, new shiny thing, and a lot of times what I've seen, especially in smaller, more nascent companies, is the founder or person who built it had that problem and then tries to go find a market.

“Whereas product marketing actually assesses the market, what sort of core competencies that organization already has, and then pulls that empathy and understanding of the market into what should we go build because we fundamentally understand there's an acute pain point going on for which people are willing to pay for a solution, and that is truly the value that a product marketing manager brings to the table.

“It's taking down the risk or lowering the risk of investing a lot of money, whether it's in people or product development or acquiring something new, and de-risking that investment”

👏🏻

How is product marketing different from other marketing roles?

Product marketing vs marketing communications

A marketing team focuses on customer acquisition and converting prospects into fully-fledged customers.

They also promote a company, an existing or new product, or a brand and ensure the consistency of the marketing message.

Product marketing, on the other hand, focuses on marketing to customers, driving demand and adoption, all with the goal of creating happy, successful customers.

Product marketing is the process of bringing a product to market and overseeing its overall success.

Product marketers are focused on understanding and marketing to customers. They drive demand and usage of the product, focusing on processes such as product positioning, sales enablement, product messaging, buyer personas, metrics, meeting customer needs, and product demos.

A product marketing team is integral to creating a deep understanding of a product’s value to the target audience and generating brand awareness.

Product marketing vs brand marketing

Brand marketing looks more at building brand awareness for a company, and ensuring that its reputation remains positive.

Though, of course, this is still a responsibility of most roles in any given organization, product marketing focuses more on driving sales of specific products that an organization has.

In short, while both roles ensure sales are carried out, product marketers look directly at what they’re selling, not who’s selling it.

Product marketing vs demand generation

Farhan Manjiyani, Product Marketing Manager at Grafana Labs, outlines the difference between product marketing and demand generation in 2 short sentences:

“If we oversimplify the marketing funnel into three stages – attract, consider, and close – demand gen focuses on stage one (attract) and product marketing focuses on stage three (close). Product marketing should inform both attracting and informing buyers through their consideration stages but should ultimately be responsible for the ‘closing’ stage.”

Product marketing vs field marketing

Kimberly Kaminski, Chief Marketing Officer at NS1 gave her two cents on the difference between product marketing and field marketing in her article:

“It’s your product marketing and field marketing teams that are in the best position to be the headlights on your road to effective demand generation. Both teams contribute valuable market-facing insights that are critical to the successful planning, development, and execution of demand generation programs and activities."

How do you get into product marketing?

The beauty of product marketing is there’s no such thing as one, set path and this is something we’ve been asking as part of our Product Marketing Insider podcasts. Without fail, this is how the conversation goes…

Us: “What did your journey into product marketing look like?”

PMM: “Oh, I had quite a windy route into the role.”

Although by no means a prerequisite or requirement, some of the most common backgrounds we hear are:

- Product

- Marketing

- Sales

- Customer Success

- Project Management

- Engineering.

If you’re looking to transition into product marketing and you’re currently at a company that has the function built-in, our advice would be to try and shadow some of their work and get as much practical experience as possible - as well as reading up on some industry resources too, of course.

Shameless but obligatory plug: our podcasts, resources, and blog are full of lots of info for newbies and experts alike.

Elsewhere, here are a few really in-depth reading materials to get you going:

- The ultimate guide to getting a job in product marketing

- How to get a career in product marketing

- What skills do I need to be a product marketer?

- Product marketing 101: Templates, strategies, and examples

Fancy yourself as a product marketing pro? Get PMA certified 👇

Follow us on LinkedIn

Follow us on LinkedIn

.svg?v=63a50ae3ef)